It’s a Snake!

By Ellen LambethIt hisses. It slithers. It’s covered in scales. Make no mistake . . .

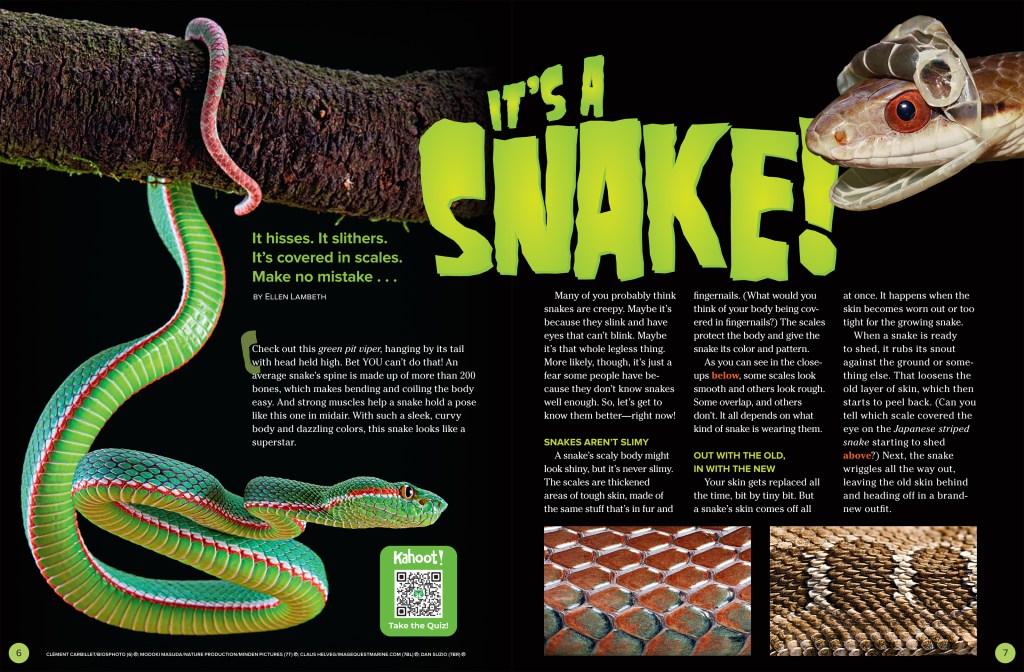

Check out this green pit viper, hanging by its tail with head held high. Bet YOU can’t do that! An average snake’s spine is made up of more than 200 bones, which makes bending and coiling the body easy. And strong muscles help a snake hold a pose like this one in midair. With such a sleek, curvy body and dazzling colors, this snake looks like a superstar.

Many of you probably think snakes are creepy. Maybe it’s because they slink and have eyes that can’t blink. Maybe it’s that whole legless thing. More likely, though, it’s just a fear some people have because they don’t know snakes well enough. So, let’s get to know them better—right now!

SNAKES AREN’T SLIMY

A snake’s scaly body might look shiny, but it’s never slimy. The scales are thickened areas of tough skin, made of the same stuff that’s in fur and fingernails. (What would you think of your body being covered in fingernails?) The scales protect the body and give the snake its color and pattern.

As you can see in the closeups, some scales look smooth and others look rough. Some overlap, and others don’t. It all depends on what kind of snake is wearing them.

OUT WITH THE OLD, IN WITH THE NEW

Your skin gets replaced all the time, bit by tiny bit. But a snake’s skin comes off all at once. It happens when the skin becomes worn out or too tight for the growing snake.

When a snake is ready to shed, it rubs its snout against the ground or something else. That loosens the old layer of skin, which then starts to peel back. (Can you tell which scale covered the eye on the Japanese striped snake starting to shed?) Next, the snake wriggles all the way out, leaving the old skin behind and heading off in a brand-new outfit.

SNAKE SENSE

Snakes don’t have ears like yours. But they can hear—just not very well. What they can do is feel the vibrations of loud sounds or of things moving along the ground nearby. For a snake, that’s as good as hearing.

Some snakes see better than others. Those with round pupils see best in daylight. Snakes active at night have cat-like eyes with pupils that can open very wide. Certain snakes, such as pit vipers, also can “see” with their heat-sensing pits (see circle). Special nerves in the pits pick up body heat from warm-blooded prey nearby. The nerves send a message to the brain, forming a “picture” of the prey.

And what’s up with snakes sticking out their tongues? All the better to smell with! A snake can use its nostrils to smell. But it can smell much better with the help of its forked tongue. The tongue “tastes” odor chemicals from the air and ground, then slips back into the mouth. There, the tips transfer the odors to two openings in the roof of the mouth. The openings lead to a special smelling organ.

TIME TO EAT!

All snakes are meat-eaters. But how do they catch their prey? Some kinds just grab it with their mouths and gulp it down. Their backward-pointing teeth (see skeleton) help keep slippery or squirming victims from escaping. And to make more room for large prey, a snake’s lower jaw isn’t connected in front as yours is. That lets the mouth open wider from side to side. At the back of the mouth, the connections between the upper and lower jaws are very stretchy. And that allows the mouth to open way up.

Certain snakes, such as the rattlesnake, inject venom into their prey through special teeth called fangs. The venom kills or stuns the prey, making it easier to swallow. Most snakes are not venomous, though. And any that are, aren’t coming for you! Just be aware of which ones live in your area and leave them be.

Other kinds of snakes, such as the African mole snake, have a different way of getting a meal. They coil around their prey and squeeze it to death.

NO FEET? NO PROBLEM!

Snakes manage to get around with ease. Some can even zig-zag across the ground at record speeds. Here are snake tricks of the traveling kind:

Wriggling This is the most common way to go. The snake moves forward by pushing against things in its path, first with one side of its body and then with the other. That works on the ground or for climbing on a tree’s rough bark, as this three-banded bridled snake is doing (1).

Another trick for climbing a tree is moving like an accordion. The snake first bunches itself up in tight curves. Then, using its belly scales to hold on with its back end, it pushes the front end upward. Finally, it holds on with the front end, pulls up the tail, and starts over again.

Creeping To go slow in caterpillar fashion, a snake straightens out and lets its belly scales (2) do the walking! The edges of the scales take turns grabbing the ground. As the scales hold on and then let go, one after another, the snake inches its body forward. The belly scales act as a series of tiny marching feet—or like the treads on a heavy tank or construction vehicle.

Sidewinding To move across loose desert sand, a sidewinder (3) crawls with parts of its body lifted off the ground. The head lifts up, and the body follows in a kind of looping action. As you can see, sidewinding leaves a one-of-a-kind track in the sand!

Swimming All snakes can swim by wriggling in the water as they do on land. Most skim along the surface with their heads held up. But they can also swim underwater. That’s especially true of aquatic snakes—those that spend a lot of time in water.

Then there are sea snakes, such as this one (4). These snakes live most—or all—of their lives underwater, coming to the surface only to breathe. Most kinds also have flattened, paddle-like tails for easy cruising.

FlyIng A few kinds of snakes can sail through the air from tree to tree! A flying snake (5) doesn’t really fly—it glides. After crawling up a tree and out on a limb, it hangs by its tail. Then it “takes off,” with its body waving in curves through the sky, down to a nearby tree. It also spreads out its ribs, which flattens its body like a kite.

THEY COME IN ALL SIZES

There are at least 3,600 different species of snakes in the world. With so many kinds, it’s no surprise that some are tiny and others are huge.

The smallest are the blind snakes. As you can see above right, one of these looks more like a worm than a snake. The world’s longest snake is the reticulated python (left). It can be longer than a two-story house is tall! And the biggest, heaviest snake overall is the green anaconda (below). How’d you like to help hold one of those?

FROM BEGINNING . . .

Some mother snakes lay leathery eggs, while others give birth to live young. All the baby rattlesnakes came out of their paler-colored mom as mini versions of her. Mom may stay in this squirmy nursery for a while. But the babies can fend for themselves and will soon head out on their own.

A few kinds of egg-laying moms stay around to protect their eggs. But most egg-layers just lay ’em and leave ’em. You can see a baby eastern ratsnake hatching from its egg.

. . . TO END

Snakes are very successful survivors. But sometimes, their luck runs out. As you see, this one was no trouble for an African ground hornbill. And some snakes even eat other snakes. That’s just life in the legless lane!

TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE ABOUT SNAKES. PLAY KAHOOT!