Seabird Chicks Hatch From Eggs

BySeabird chicks hatch from eggs, just like land birds. One difference between seabirds and land birds is land birds usually nest alone. Most seabirds nest in large groups, or colonies, on remote islands. Islands make perfect nesting sites for seabirds because there are few ground predators to disturb them—although sometimes eggs and chicks get eaten by other seabirds.

Seabirds are excellent and watchful parents, feeding and guarding their chicks until they are ready to leave the nest. Cold, heat, predators, and starvation are all life threatening for young chicks. But if they are hardy enough to survive their first year, they may live for 30, 40, or 50 years. The oldest known seabird is a Laysan albatross, named Wisdom, who laid and hatched an egg at the age of 70! Experts estimate she has probably raised more than 30 chicks in her lifetime.

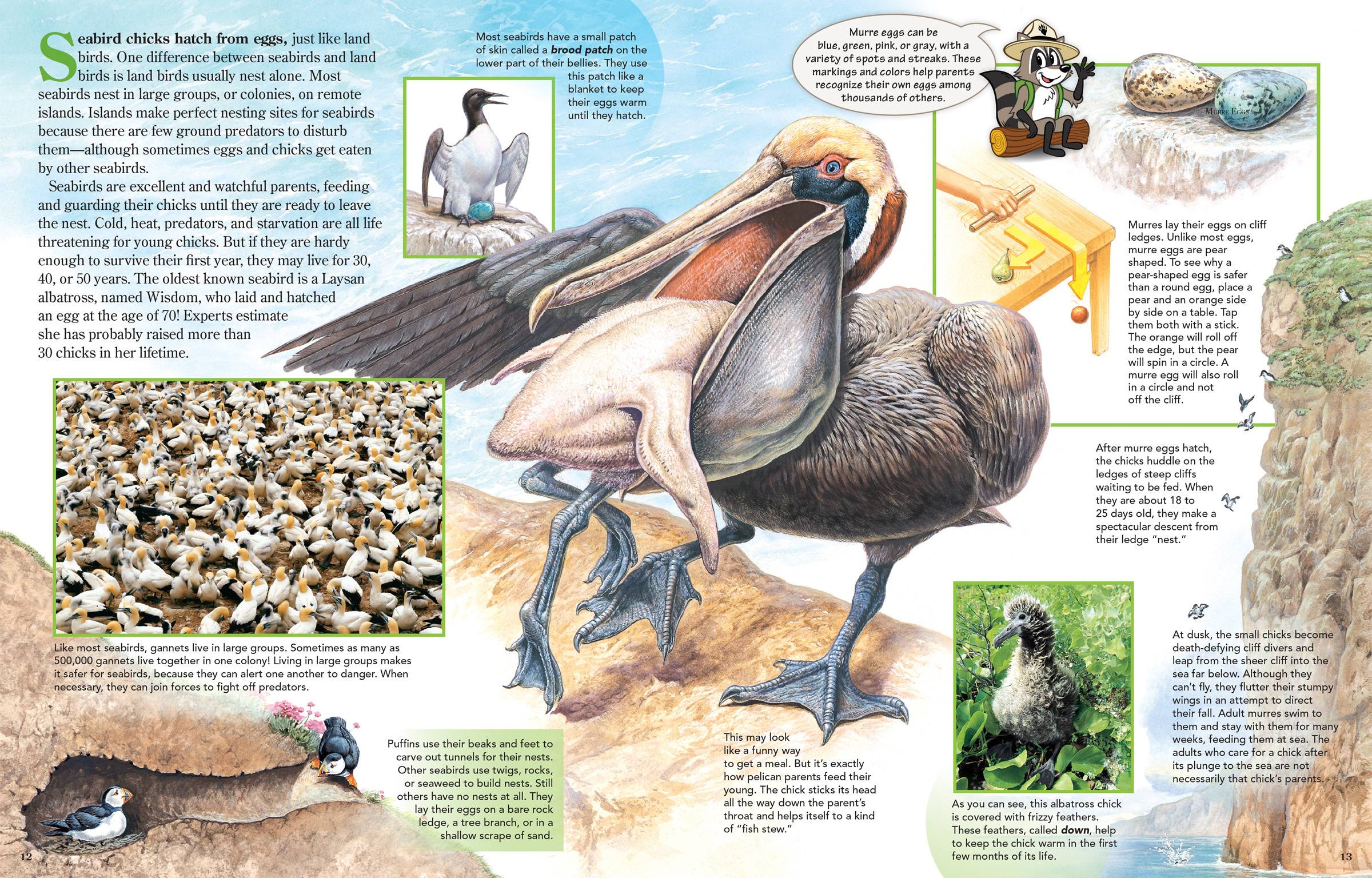

Most seabirds have a small patch of skin called a brood patch on the lower part of their bellies. They use this patch like a blanket to keep their eggs warm until they hatch.

Like most seabirds, gannets live in large groups. Sometimes as many as 500,000 gannets live together in one colony! Living in large groups makes it safer for seabirds, because they can alert one another to danger. When necessary, they can join forces to fight off predators.

Puffins use their beaks and feet to carve out tunnels for their nests. Other seabirds use twigs, rocks, or seaweed to build nests. Still others have no nests at all. They lay their eggs on a bare rock ledge, a tree branch, or in a shallow scrape of sand.

Murre eggs can be blue, green, pink, or gray, with a variety of spots and streaks. These markings and colors help parents recognize their own eggs among thousands of others.

Murres lay their eggs on cliff ledges. Unlike most eggs, murre eggs are pear shaped. To see why a pear-shaped egg is safer than a round egg, place a pear and an orange side by side on a table. Tap them both with a stick. The orange will roll off the edge, but the pear will spin in a circle. A murre egg will also roll in a circle and not off the cliff.

After murre eggs hatch, the chicks huddle on the ledges of steep cliffs waiting to be fed. When they are about 18 to 25 days old, they make a spectacular descent from their ledge “nest.”

At dusk, the small chicks become death-defying cliff divers and leap from the sheer cliff into the sea far below. Although they can’t fly, they flutter their stumpy wings in an attempt to direct their fall. Adult murres swim to them and stay with them for many weeks, feeding them at sea. The adults who care for a chick after its plunge to the sea are not necessarily that chick’s parents.

This may look like a funny way to get a meal. But it’s exactly how pelican parents feed their young. The chick sticks its head all the way down the parent’s throat and helps itself to a kind of “fish stew.”

As you can see, this albatross chick is covered with frizzy feathers. These feathers, called down, help to keep the chick warm in the first few months of its life.